November 9, 2022

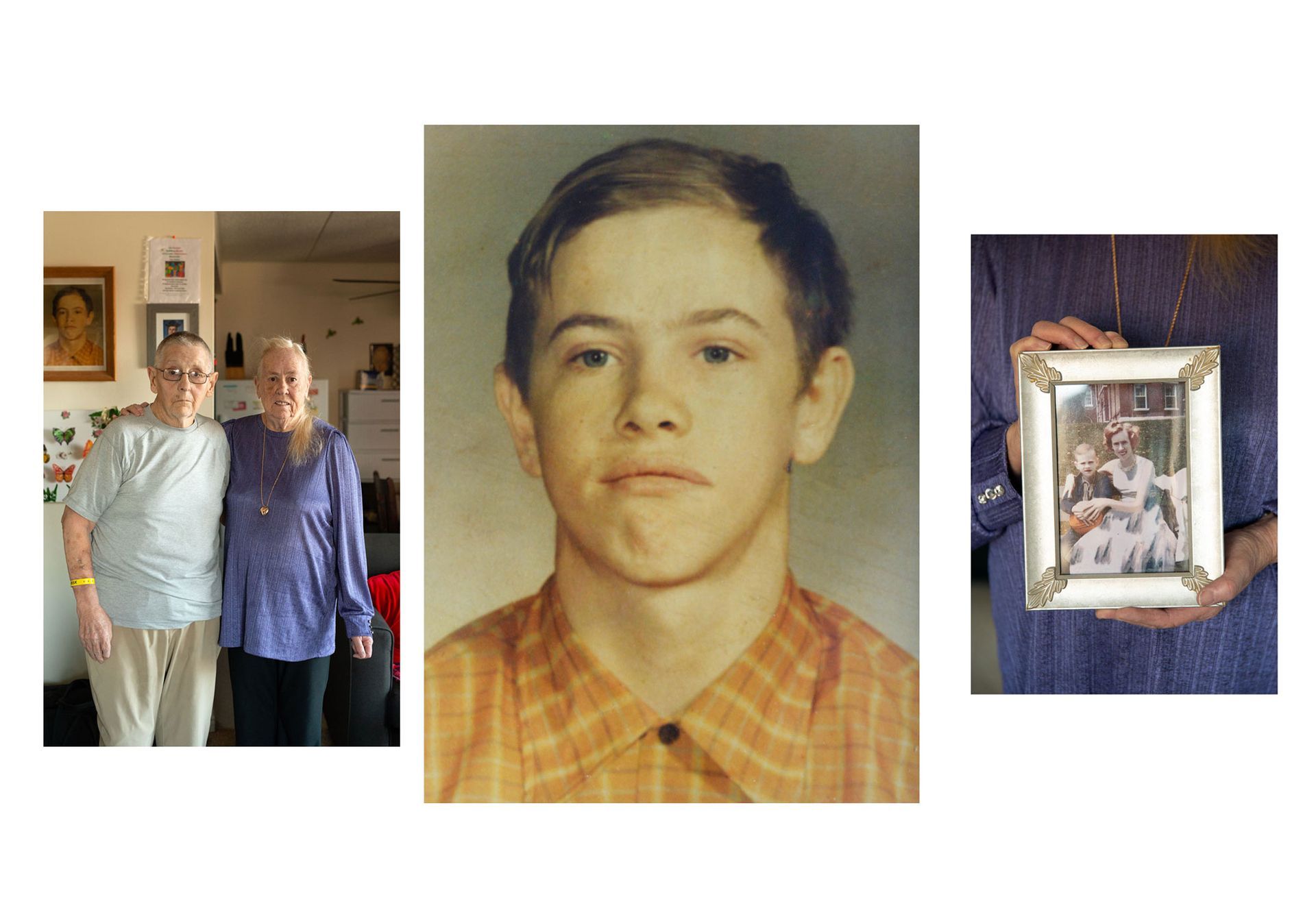

In July 2021, survivors of the Child and Parent Resource Institute (CPRI) – once known as the Child Psychiatric Research Institute – settled a $12 million class-action lawsuit out of court. It was the seventh and – according to Koskie Minsky, the class-action law firm representing survivors – “likely last” class action between survivors of provincially operated residential institutions for people with disabilities and the Ontario government. Each of these seven lawsuits has unveiled horrific accounts of violence, neglect, and abuse of disabled people incarcerated in these institutions. In Ontario’s institutions, survivors recount being locked in metal cages, forced to haul gravel without pay, and beaten by staff. They wanted justice – which, for many, included financial reparations, government apologies, and for the government to never again run institutions for disabled people. Class-action lawsuits are one way for groups of people to pursue justice after shared experiences of harm – and on the surface, they seem like a good way for survivors of institutional abuse to get the restitution they deserve. But in looking closely at class-action lawsuits for survivors of institutions in Canada, justice remains elusive. Hearing their stories The CPRI settlement in July 2021 would be different from earlier settlements for survivors of provincial disability institutions. This time, there would be no apology from the government. The institution would remain in operation. Survivors who were “class members” in the class action would be put under a stringent communication ban, which barred them from sharing or archiving their experiences at CPRI. That meant there would be just one chance to listen to their stories. Alone in my apartment, I log in to the CPRI settlement agreement hearing. This glitchy Zoom call is the only opportunity for survivors to publicly share what they endured while incarcerated in an institution that promised to care for them. For a few short minutes, the chat function was a place of community and solidarity. It served as a memorial. “good morning to all who are here finally getting restitution. 8 months of torture for me. Much love to alll that were there” “I was never the same after that fucking place” “Me either. Fucking monsters” The reasons disabled people – and those labelled as such – are forced to live in institutions differ. Some begin living in institutions because of a lack of available resources to support them surviving in their community. For others, the label of “intellectual or developmental disability” is used as justification to expand the incarceration of people whom the Canadian government deems “degenerate”: largely Indigenous, poor, and racialized people. “The psychiatrists tried to put me down by labelling me ‘schizophrenic’, ‘psychopathic’, and ‘violent,’” recalls Mohawk psychiatric survivor Lionel Vermette in the 1988 collection Shrink Resistant: The Struggle Against Psychiatry in Canada. “The guards attacked my Native identity. They all failed. I’m not a bad person. I’m not violent. I’m an Indian, a good Indian, and I am very proud.” Institutional scholars Kate Rossiter and Jen Rinaldi use the term institutional violence to describe the widespread abuse, sexual sterilization, corporal punishment, public humiliation, medical experimentation, solitary confinement, and torture that happens inside places like the CPRI. It means that the violence is not an accident, but a deliberate and inherent feature of government-run institutions. “I was locked in padded rooms till i peed myself starved and more needles of ‘calm me down’ fluid i can remember and many beatings” “I can’t possibly imagine the number of ppl who have committed suicide because of what happened” The clerk closes the chat function. I light a cigarette from the solitary pack I keep at the back of my closet, reserved for the news of another Mad suicide. How many cigarettes does one smoke for the uncountable? Over the last decade, I have organized and researched alongside survivors of institutions for disabled people, and written about their legacies in policy, media, and social movements. It’s gut-wrenching work that involves paying close attention to disabled death: the 20,000 people killed in institutions like long-term care homes during COVID-19, the endless inquiries into deaths in group homes, the bodies in institutional cemeteries. Much of the information about institutions – like the number of people who died there, number of COVID-19 outbreaks, use of restraints, and even the number of people incarcerated inside them – is not publicly available and is often shielded from even the most savvy Freedom of Information requests by thick walls of medico-legal bureaucracy. In other words, out-of-court settlements obscure the harms of these institutions, and they often run counter to the demands of survivors for accountability, transparency, and closure. So, class-action lawsuits are pointed to as one of few windows into the institutions that confine disabled people. In the U.S., class actions against large-scale institutions have exposed the systemic violence of institutions, and in some cases have led to their closure. Abolitionist disability scholar Liat Ben-Moshe refers to these cases as “abolition litigation.” Rather than trying to reform institutions, Ben-Moshe writes, “lawyers did not just seek reparation for or change in the conditions of institutions but sought to prove that these carceral locales are inherently unnecessary and unconstitutional, and therefore need to be closed altogether.” In Canada, class-action lawsuits against institutions for disabled people have produced different results. Here, 100 per cent of these class actions have been settled out of court. This means the lawsuit never goes to trial – and it’s largely through trials that institutional documents are released and survivors’ testimonies are entered into the public record. In other words, out-of-court settlements obscure the harms of these institutions, and they often run counter to the demands of survivors for accountability, transparency, and closure. Bound to an agreement Class actions are used to remedy a wide variety of harms. Two of the largest class actions in Canadian history show the range of injustices they address: the ongoing lawsuit against Loblaws and other bread sellers for their role in price fixing bread for Canadian bread purchasers between 2001 and 2021, and the $1.9 billion settlement for survivors of abuse at Indian residential schools. Class actions work pretty well in getting consumers financial reparations for corporate schemes like price fixing, especially when it would be too difficult and expensive for every individual consumer who was affected to launch their own lawsuit against the company. But they do not guarantee the systemic changes that would put an end to the practices that caused plaintiffs to sue in the first place. This was abundantly clear in the class action of survivors of residential schools against the Government of Canada. Fifteen years after the settlement, survivors and their descendants continue to face relentless roadblocks in accessing records about residential schools from the federal government and the Catholic Church. As class members, survivors of abuse are often bound by non-communication rules that prohibit them from speaking out about their negative experiences. Lawyers from the Class Action Clinic at the University of Windsor point to another barrier to accessing justice. In, Canada class members are automatically included in a class action unless they opt out. Class members are the people belonging to the group affected by the allegations against the defendant – for example, anyone who bought price-fixed bread from the eight big Canadian bread sellers in the last 20 years. Frequently, the window to opt out of being a class member expires before the settlement agreement hearing even begins. This means that many people don’t even realize they are class members, but after the class action, they can no longer individually sue for damages. As class members, survivors of abuse are often bound by non-communication rules that prohibit them from speaking out about their negative experiences. There’s also a window of opportunity for class members to claim money. In the instance of CPRI, class members had nine months after the court approved date to file a claim. Many survivors of abusive institutions are unhoused or precariously housed; others have been moved into new institutions like prisons, long-term care facilities, and group homes. When class members are hard to contact, they may find themselves bound to an agreement – or owed money – they don’t even know about. Once class members have been notified of a settlement, they can make a claim and potentially access settlement money. In the CPRI settlement, the amount of money a class member would receive was determined by a complex point system that set out to determine the severity of the abuses they experienced. To prove that they were abused, survivors had to provide medical records and a sworn affidavit. But for disabled people who do not use verbal communication, they were often not given the necessary tools – like letter boards or tablets – to articulate their experiences. At the CPRI settlement agreement hearing, survivors spoke to the absence of records in these cases. “Reason i disagree with the settlement is that there were a lot of kids there who can’t speak for themselves, they can’t tell you what happened to them. But i saw it firsthand.” “This settlement means you have to have been hospitalized – but there were doctors on staff, so a lot of it was taken care of there.” “For all the people who can’t speak, it is hard. I have found it hard not to cry for others, for myself.” The Huronia settlement Over a decade before the CPRI settlement, a lawsuit against the Huronia Regional Centre was filed by survivors Patricia Seth and Marie Slark after reuniting at Marilyn Dolmage’s kitchen table. Seth and Slark were dropped off at Huronia when they were six and seven years old, respectively, and they remained there for almost 15 years. During that time, Dolmage had worked as a social worker at Huronia and had stayed in touch with the two women. Huronia was opened in 1876 in Orillia, Ontario – first as the Orillia Asylum for Idiots, later renamed the Ontario Hospital School, then the Huronia Regional Centre. It was the first institution for people labelled with intellectual or developmental disabilities built in Canada. Within its first 100 years, 4,000 children and adults died there. While institutionalized, Seth and Slark endured horrific abuse: they were locked in metal cages, sexually and physically abused by staff, and watched while in the washroom. Together, they decided to launch a class-action lawsuit in 2007, with Dolmage and her husband Jim acting as litigation guardians. Under law, disabled people who are labelled “incapable” are not permitted to launch a legal action or direct their lawyers, so litigation guardians can help give instructions to lawyers and support disabled claimants. “When you have an intellectual disability it feels like most people don’t care about [your] opinion, especially if you are poor,” Seth tells me. “And most of us live in poverty.” This idea of “capacity” is foundational to the legal system and it forms the basis for what researcher Sylvia McKelvie dubs legal ableism. Legal ableism encompasses the ways in which the legal system discriminates against and removes agency from people with disabilities. Seth and Slark’s experience of the class action was marred by systemic and legal ableism – even with their own lawyers. “When you have an intellectual disability it feels like most people don’t care about [your] opinion, especially if you are poor,” Seth tells me. “And most of us live in poverty.” “We know what it’s like to be intimidated,” Slark adds. “To have authority figures over us.” Class actions begin with a certification hearing, where the court approves the case as a class action and approves the lawyers as the representatives of the plaintiffs and defendants. After the certification hearing in 2010, Seth, Slark, and the Dolmages’ relationship with their lawyers at Koskie Minsky – the same class-action law firm that would go on to represent survivors of CPRI – quickly deteriorated. When I speak to the Dolmages, they say that once the certification hearing was over, they were aggressively “bullied back and forth” by the lawyers. They explain that their lawyers applied intense pressure to Seth and Slark to prepare for trial, then switched tracks, pressuring the two plaintiffs to settle. During that time, Koskie Minsky lawyers met with government lawyers without the plaintiffs present, and they agreed to terms for a proposed settlement – terms that Seth and Slark opposed, and the lawyers refused to change. The lawyers signed the final settlement agreement without telling Seth, Slark, or the Dolmages, or even showing them a copy. And while Seth, Slark, and the Dolmages were frustrated by the process, they did win some important things: easier access to settlement funds, the right to not return unclaimed funds to the government, and a memorial for survivors. Though Seth and Slark were seeking $1 billion in damages, in 2013 the lawsuit settled out of court for just $35 million. As is common in class-action lawsuits, about half of that – $18.8 million – was claimed by survivors; $8.5 million of the settlement went to Koskie Minsky’s legal fees, $3 million went to the Law Society’s class proceedings fund, and $4.7 million went to projects that benefit survivors. And while Seth, Slark, and the Dolmages were frustrated by the process, they did win some important things: easier access to settlement funds, the right to not return unclaimed funds to the government, and a memorial for survivors. Huronia survivors could access settlement funds through one of two streams. The first was a points system, where those who experienced the most severe physical or sexual abuse could claim up to $35,000 – but in order to do so, they were required to submit a sworn affidavit and medical records. The second stream was more accessible: a lump sum payment of $2,000, which survivors could receive by simply checking a box to confirm they attended the institution. In class actions, when class members don’t fill out forms or cash cheques to claim their settlement money, the unclaimed funds are typically returned to the defendant. In the case of the Huronia settlement, $23.4 million was allocated for survivors, but only $18.8 million of that was claimed, leaving $4.6 million that would have been returned to the Government of Ontario. But Seth and Slark won the right to not return leftover funds in their agreement. Instead, they negotiated for what’s called a cy-près, where they were able to put the unclaimed settlement funds toward research and memorials for survivors of Huronia. Despite the settlement’s shortcomings, the process sparked news coverage and brought to light the horrific treatment of disabled people confined within institutions. “The settlement has been incredibly productive in terms of relationships, projects, and the opening of public discourse that has allowed a discussion of institutionalization to flourish,” says Dr. Kate Rossiter, a scholar studying institutions who has worked alongside survivors to ensure their stories are remembered. These victories set Seth and Slark’s case apart from other institutional class actions that followed. The remaining institutions Shortly after the Huronia agreement in 2013, two more class actions were filed by survivors of the Rideau Regional Centre in Smiths Falls and the Southwest Regional Centre in Chatham-Kent. Both were settled out of court, each for millions less than the Huronia settlement. But these agreements had many of the same stipulations: an option for a smaller, easier-to-access lump sum payment, an apology from the premier, and a redirection of unclaimed funds to developmental disabilities projects. In 2015, the next settlement agreement was reached on behalf of survivors of 12 additional institutions across Ontario. Settled at $36 million collectively, or $3 million per institution, this was the lowest settlement and would not come with an apology or project fund. Outside of Ontario, similar class-action lawsuits have been filed by survivors of institutions in B.C., Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and P.E.I. The Dolmages have followed these subsequent class-action settlements closely, feeling increasingly frustrated with the outcomes. “Our hopes were that the Huronia settlement would set a strong foundation for future cases,” Marilyn says. “Instead, every case has been more and more watered down.” The institution that remains In the 2021 CPRI settlement approval, the judge highlighted the similarities with the Huronia agreement multiple times – but the outcomes were very different. In the $12 million CPRI settlement, there was no option for survivors to disclose less information to receive a smaller lump sum. The CPRI settlement’s point system only included four “levels” of violence: physical assault and three levels of sexual assault. Every survivor who wanted to receive settlement funds for physical assault, or levels 2 or 3 sexual assault had to submit affidavits and medical or administrative files proving their abuse. Unlike in the Huronia settlement, the levels did not include various forms of physical or emotional abuse – corporal punishment, humiliation, and “non-severe” physical abuse. This points to the larger issue: that class-action lawsuits cannot put a stop to the harms of government-run institutions. In the end, there was no apology, no money for further research, and no opportunity for archival projects. The institution remains in operation. In 2012, only a year after CPRI was de-listed as a residential mental health institution, an autistic child was beaten nearly to death by a staff member there. He was excluded from the class action. This points to the larger issue: that class-action lawsuits cannot put a stop to the harms of government-run institutions. “We’re not done fighting yet” Most class-action lawsuits settle out of court. Research by Jasminka Kalajdzic, author of Class Actions in Canada: The Promise and Reality of Access to Justice, reveals that in Ontario, where there have been over 500 class-action lawsuits, only 18 have gone to trial. Kalajdzic argues that out-of-court settlements obscure the harms of institutionalization experienced by both survivors and those who died while incarcerated. There are no public hearings, and the records of the harms tend to remain inaccessible. Cindy Scott is one of the many Huronia survivors fighting back against the insufficient class-action settlement agreement and the government that failed to keep the promises it laid out in its 2013 apology to survivors. “The government got away with it. They killed people,” Scott says. “The government should be ashamed of themselves.” Scott is a member of Remember Every Name, a Huronia survivors’ organization working to fill in the gaps in knowledge about those who died at Huronia. Before 1958, most of the grave markers in Huronia’s cemetery bear only a number – the order in which people died – and no name. Some grave markers from before 1930 have been removed entirely. Today, no one knows for sure how many people are buried at Huronia – certainly at least 1,379, but likely more than 2,000. A photo of a large black stone monument, with words engraved on the front. It's standing on a green lawn and surrounded by a dozen people, including a person in a wheelchair, a number of children, and one person who is reading from a paper. In 2015, Remember Every Name found out that a sewage line had been built through the cemetery of the Huronia Regional Centre decades ago, which may have disturbed graves. Survivors have also protested the government’s memorial, which was built as a condition of the settlement. Survivors have noted inaccuracies in the plaques designed to memorialize people buried in the cemetery. So, Remember Every Name used the unclaimed funds from the settlement to create their own memorial – to this day the only institutional memorial approved by survivors in Ontario. Sarah Jama, co-founder of the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, says the way class-action settlements have played out is part of a bigger culture of secrecy around government-run institutions. “Governments of all jurisdictions in so-called Canada continue to try to bury the deep harms and the violence perpetuated by the state through these publicly funded institutions,” she remarks. Today, institutions remain an ongoing reality in the lives of disabled people, particularly those labelled with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Scott points to long-term care institutions as one place where disabled Canadians are still confined – and where at least 20,000 people died during the pandemic. The underlying goal of institutions remains constant: isolate and segregate disabled people at the lowest cost possible. In the words of late disability radical Marta Russell, “Though transfer to nursing homes and similar institutions is almost always involuntary, and though abuse and violation within such facilities is a national scandal, it is a blunt economic fact that, from the point of view of the capitalist ‘care’ industry, disabled people are worth more to the Gross Domestic Product when occupying institutional ‘beds’ than they are in their own homes.” Talking with Marilyn Dolmage, Cindy Scott, and Sarah Jama, the path forward seems clear. We need a future free of institutions, with supportive and well-resourced communities in which disabled people can thrive. Though class actions can win some restitution for survivors – money, apologies, and media coverage – they haven’t brought us much closer to this just future. ______ Article written by Megan Linton Megan Linton is a disabled writer, researcher, PhD student and creator of Invisible Institutions , a documentary podcast and research project exploring the past and present of institutions for people labelled with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Canada. Find her on Twitter at @PinkCaneRedLip . Source: https://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/class-inaction